A quick introduction to story mapping

A serious issue with agile is the lack of the “big picture.”

Agile breaks larger requirements into smaller chunks or “stories.” These stories are quick to develop and enable users to get a rapid view of progress as the stories are completed in a series of short sprints.

One possible downside to agile is that, when looking at a list of many stories in different backlogs, it is easy to lose the big picture of what the system should do. An analogy would trying to see a tree by only looking at the tree’s leaves. All too often, many small stories developed over a period of time do not come together as a coherent system.

A house of many colors

Losing sight of the big picture is like having each room in a house painted by decorators who did not have clear direction about who lived in the house and the outcomes they need. If the decorators miss the big picture of what the family needs – for example, a kid-friendly, low-maintenance décor – the house owners would get a new paint job, but the results are unlikely to please, since the colors might not meet with expectations. Worse, if the finish is not low maintenance or easy to clean, it is not even fit for purpose and not likely to last long in a family environment.

Too many systems are developed in this way, where there is no shared understanding of the big picture in terms of business outcomes and how users will use the finished system. At best, these systems have mediocre benefits and, at worse, a negative effect on the business and users who refuse to use the system.

The change of focus from the business and users to documents

Another common problem with agile methods is that stories are treated as one-way communications between business analysts and programmers. To paraphrase Martin Fowler, this is a serious mistake; stories are intended to spark a conversation between the business and developers. A central tenet of agile is collaboration between business and developers – this concentrates the developers’ ability to get the best out of software tools and the in-depth knowledge of what the business needs.One-way communication compounds the problem of the team not seeing the big picture. Even if the product manager and BAs are on the same page as the business users, the lack communication with the rest of the team will make the project unlikely to succeed in terms of business impact.

Where stories are just requirements documents by a different name

In many organizations stories are used simply as a stand-in for the traditional requirements document, and usually the development process resembles the old waterfall methods with all its associated problems.The result is a lack of common understanding between stakeholders and all the parties responsible for producing the software, resulting in software that is over budget and has a disjointed set of features that pleases no one and provides little or negative business impacts.

“The days of product managers gathering up and documenting requirements, designers scrambling just to put some lipstick on the product, and engineers sheltered in the basement coding are long gone for the best teams – and it’s time they were gone in your team, too.” – Marty Cagan Getting to a better place: change your mindset. The most important point is to shift your mindset from the idea of building more software faster, to maximizing the outcomes and impact of what you build. Too many organizations focus on team velocity, stories completed and releases made. That only adds up to going in the wrong direction faster.

Work with your users

To do this, you need to identify useful outcomes for the business – things that will have a positive impact. Wherever possible, try to work with the people who will actually be using the system. Failure to clearly identify business outcomes means that you cannot identify the value for stories or understand stories that belong together to satisfy some outcome. If you do not know the value of stories or their relationships, you cannot effectively plan a release or manage scope when deadlines are tight.

To gain a deep understanding of the business, you have to collaborate with the people in your business. You need to develop a model that represents how things are now (this can be extended to the later/target model). Your objective is to understand what tasks people perform to achieve the desired outcome, in terms of what happens and when things are done for a specific business outcome.

By working with different business users, alternatives can be identified as well as what happens when things go wrong. When holding these discussions, take notes and take pictures, these resources help act as a “anchor” to help people recall the whole discussion.

Present information in an accessible way – it is about shared understanding Story maps are a great way of bringing all the information together in a way that everyone can understand and participate in. It is easy to see who is involved, what happens now, where pain points are and what improvements can be made.

Story maps provide clear links to users and business outcomes. They keep focus on the business needs and impact, so it is possible to separate what needs to be done to satisfy some specific outcome, or the outcomes needed to enable a certain group of users. The result is a better collaboration and ultimately, a better product. They enable the team to minimize output while maximizing outcomes and impact.

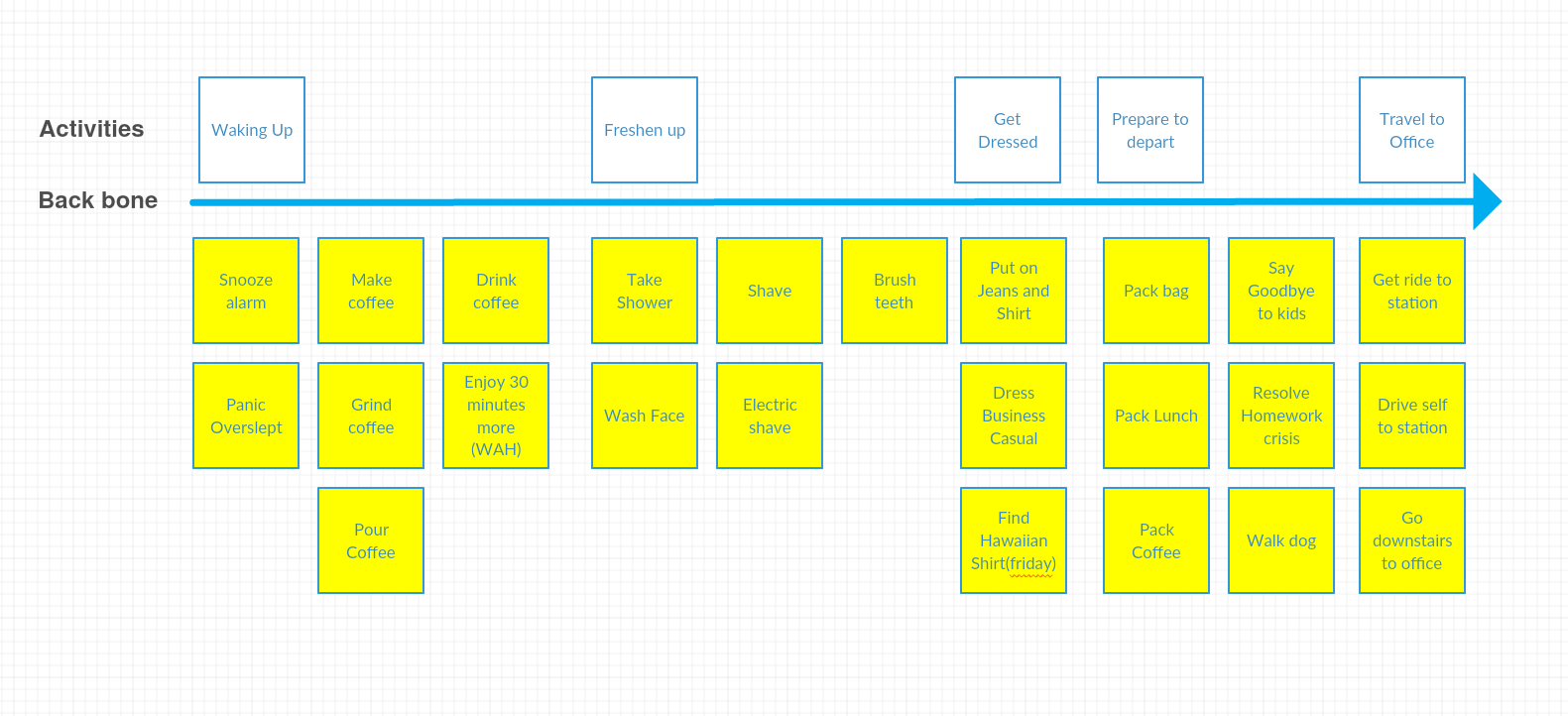

To make a story map you would write a short verb phrase on a post-it note for each of the activities and tasks you identify when collaborating with the business. These post-its can be put on a white board as a narrative, flowing from left to right. It should be easy to point to the board and see and talk about the sequence of tasks.

If you work with a group, different people will achieve their tasks in different ways. Plus you can identify what happens when things do not go according to plan. These alternatives, actions and tasks can be grouped together, one below the other.

Avoid using a system at this point – your mission is collaboration. It has to be easy to move tasks around, regroup things as a group of people. You can easily record different stages using your smartphone.

If you look at the tasks, some will naturally belong together to form some larger task. This larger task is called an “activity” (also defined by a simple verb phrase).

In summary, you can think of story map as a grid. Along the top of the grid, flowing from left to right, are activities. For each activity there will be one or more tasks that people do to complete the activity. Each task is defined by a short verb phrase. The depth of the map contains the variations and alternative tasks for some activity. Tasks are arranged from left to right in a narrative flow.

Slice out releases

You need to accept that you can never do it all, so focus on some specific outcomes to prioritize what is done in terms of impact to the business. Alternatively, choose a particular user (or group) that needs to be satisfied first. If you cannot identify specific outcomes then you cannot prioritize.

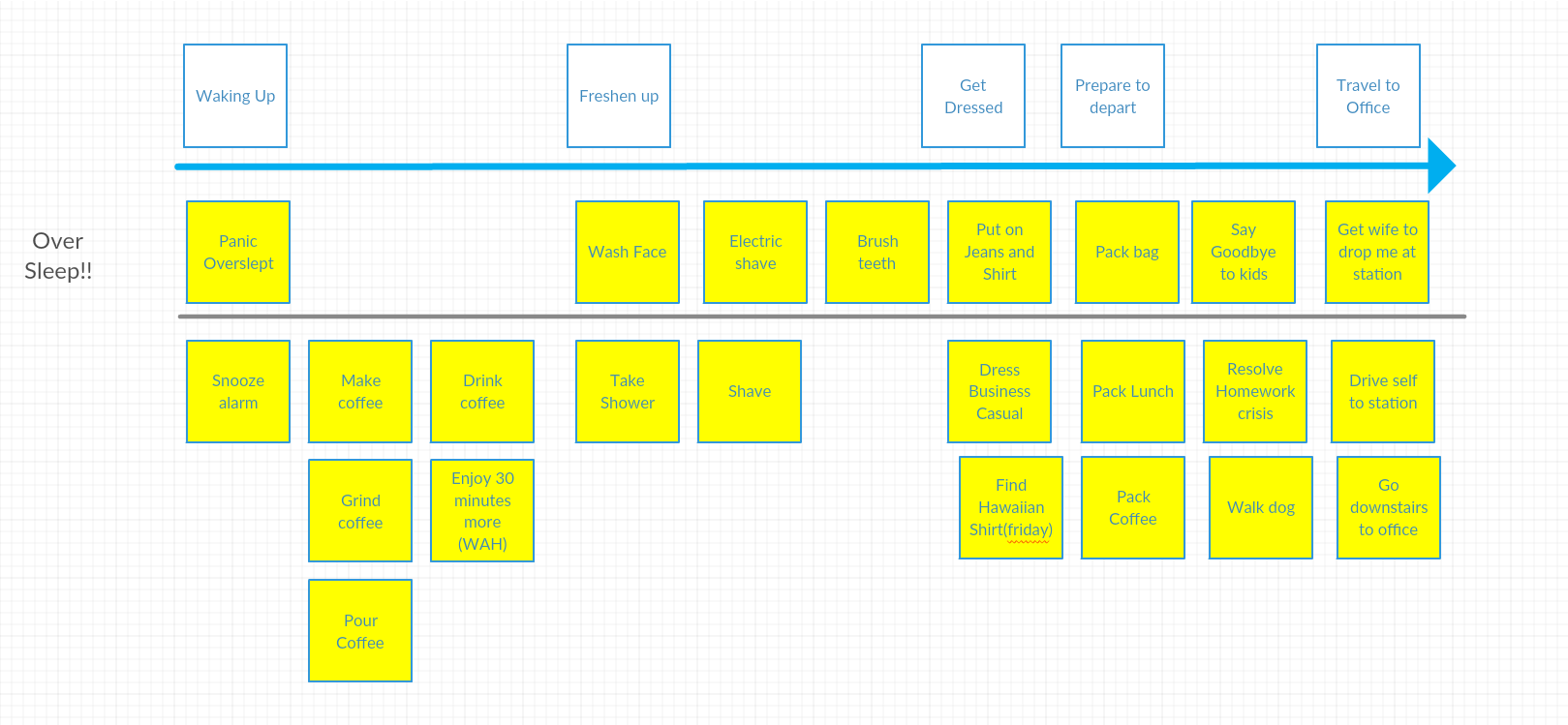

Story maps are good tools for separating tasks to satisfy some outcomes from the full set of tasks. You can slice the map into sections or rows below the map to capture the tasks needed to reach a specific outcome or group of users. There are different ways you can slice the project: you could incrementally add function in a series of releases (see above), pick certain activities and outcomes, or select a group of activities for some specific users. In our example the most minimum case happens when someone oversleeps.

Because all the tasks are still present, you keep the view of the big picture, but can focus on what is needed for some business outcome. In our example, the minimal tasks for getting to work are shown as what happens when the alarm does not work and I’ve overslept.

If you break things up by releases, consider that the minimum viable solution (MVS) is the smallest solution release that successfully achieves its outcomes for a user or group of users.

That said, it is very hard to make a single release that will satisfy the business’s outcomes in the first attempt. So another use for MVS is as a learning tool to discover what really would be a minimal release by presenting the MVS and gaging reactions from a small set of your users as part of a process to get to the real product – see Eric Ries book The lean startup.

What’s the story – stories are about collaboration and sharing knowledge

When using story mapping, the activities and work items in the vertical slices correspond to the stories in Scrum. Stories are not intended to be a written form of requirements – they are discussions and records of collaboration about solving problems with the emphasis on collaboration. Good stories provide a shared understanding of who uses the system, what they need to do and how the story satisfies business outcomes that create positive impact. They should be augmented with pictures, notes and text to anchor ideas in the participants heads to underscore their role as tools to communicate.

What’s next?

If you have made the shift to increased collaboration and to using tools like story mapping to focus on business outcomes and share knowledge throughout the team, you have set the stage for great delivery and business impact. Story mapping as a technique is kept simple and accessible to all the stakeholders in a given venture. To execute and deliver based on a clear view of what the business really needs, you still need to lever the innovation and skill that the engineering team brings. Story mapping does not help your team develop faster or use better internal engineering practices; rather, it ensures that what they develop is actually useful.

That said, you should access some great resources to understand the best ways to translate the collaborative work depicted in story mapping into your development process.If you have read this far, then it’s a must to read User Story Mapping: Discover the Whole Story, Build the Right Product by Jeff Fuller, which covers all the topics from creating story maps to how we get them executed.